In Iran, the idea of “spring cleaning” isn’t just a seasonal excuse to gut your closet; it’s the basis of a national holiday dating back millennia.

Every year, millions celebrate Persian New Year, or Nowruz (prounced “no-rooz”). In Iran, the new year begins with the advent of spring, and most everyone in the country — not to mention the millions of Iranians and non-Iranians who celebrate the holiday elsewhere around the world — observe it by doing a deep clean of their homes, celebrating a season of new life, and wishing for good luck in the year ahead.

You might have heard about Nowruz peripherally. The United Nations formally recognized it as an international holiday in 2010; President Obama extended Nowruz greetings to observers every year of his administration since 2009 (although they often doubled as statements on the relationship between the United States and Iran). Then-first lady Michelle Obama even held a Persian New Year celebration at the White House in 2015, complete with the Obama family’s own haft-seen (more on what a haft-seen is later).

If you didn’t grow up celebrating Nowruz like I did, though, the concept might be confusing — actually, it was even a little confusing for me, since my childhood memories of Persian New Year mostly concerned salivating over the delicious rice dish my mother would make in its honor.

But once I started to learn more about what Nowruz means outside of food — which, to be fair, is an important part of most holidays on this planet — I realized how fascinating its layered traditions really are.

What is Nowruz?

Nowruz marks the end of the old year and the beginning of a new one, and it occurs on the day of the vernal equinox.

More accurately, the new year begins the second the equinox does — so, not just at the stroke of midnight. Usually, the equinox happens from March 19 to 21; this year, Nowruz lands in the evening of March 20. (Though if you’re an expat Iranian, the equinox arrives around 12 pm Eastern.) But there are also aspects of Nowruz that permeate Persian culture for weeks leading up to the holiday and even a couple of weeks afterward.

No one knows exactly how far back Nowruz dates. The best estimates sit somewhere in the range of 3,000 years. But the most important thing to know about Nowruz’s origin story is that it’s rooted in Zoroastrianism, an ancient Persian religion that predates both Christianity and Islam. (Since Zoroastrianism dates back thousands of years, it’s hardly confined to within the borders of Iran or the many versions of the Persian Empire there have been — which is why Nowruz is also celebrated by millions of non-Iranians around the world.)

When the 1979 revolution ended with Persia becoming the Islamic Republic of Iran, the new government tried to scale back the level to which Nowruz is celebrated, citing the holiday’s pre-Islamic roots as grounds for its removal. But even in a nation that was fragmented to the point of revolt, the prospect of losing Nowruz prompted furious pushback that was too overwhelming to brush aside.

After thousands of years in the making, Nowruz remains too beloved, universal, and deeply embedded in Persian culture to ignore.

And because the holiday has been around for so long, it suffers no shortage of related traditions. But there are nevertheless a few basic, foundational tenets that nearly everyone who celebrates Nowruz — in Iran and elsewhere — upholds.

How do you prepare for Nowruz?

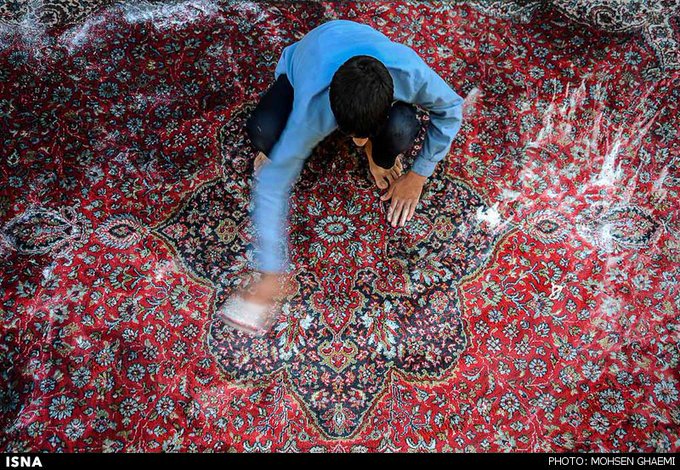

People start getting ready for Nowruz about three weeks before the actual vernal equinox. Pretty much everyone goes into serious spring-cleaning mode, ridding their homes of any unnecessary clutter and lingering grime that’s settled in over the past year so they can start fresh. At this time of year in Iran, you’re likely to see countless Persian rugs hanging outside, where their owners can beat the dust out of them.

Washing away the dust of the previous year.

Nowruz khaneh tekani (cleaning), North #Khorasan province, Iran.

In these same weeks leading up to the actual day, families also set aside a space for a “haft-seen,” or a collection of items that symbolize a different hope for the new year. While some families add their own variations to the haft-seen (more on those in a bit), there are seven things that are always included:

- Sabzeh: Some kind of sprout or grass that will continue to grow in the weeks leading up to the holiday, for rebirth and renewal

- Senjed: Dried fruit, ideally a sweet fruit from a lotus tree, for love

- Sib: Apples, for beauty and health

- Seer: Garlic, for medicine and taking care of oneself

- Samanu: A sweet pudding, for wealth and fertility

- Serkeh: Vinegar, for the patience and wisdom that comes with aging

- Sumac: A Persian spice made from crushed sour red berries, for the sunrise of a new day

While these seven S items are the foundation of a haft-seen (which literally means “seven S’s”), the tradition has evolved to the point where there are several other things you can include. For example, when I was growing up, my family’s haft-seens always included a mirror symbolizing reflection, colored eggs for fertility, coins for prosperity, and, if we were feeling ambitious, a live goldfish for new life (an ironic association in my house, where pretty much every goldfish we brought home died immediately).

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10453377/nini_haftseen.png)

Once you have the seven cornerstones set, the haft-seen is yours to customize. Muslim families will sometimes include a Quran. Sometimes a place of honor will go to a volume of poetry by Hafez, one of Iran’s most beloved poets.

Once the day of Nowruz arrives, it kicks off a 13-day celebration of dinners, family visits, and reflections on the year ahead. On the 13th day, you take the sabzeh that’s been growing in the haft-seen to whatever natural body of running water you can find and let it float away, to release the old and usher in the New Year.

My mother, who grew up in Tehran, told me that Nowruz usually saw everyone piling their sabzeh into their cars to head off into the mountains, the better to find a water runoff to set their greens adrift. And even though that meant braving a traffic jam like none other, everyone did it.

But Nowruz isn’t all about cleaning and plant life; other rituals involve fire, money, and — stay with me — banging on pots with spoons

Though my family always assembled a Nowruz haft-seen, I grew up in New Jersey without many other Iranians around, so we couldn’t indulge in some of the more communal traditions — which is a shame, because they sound fun.

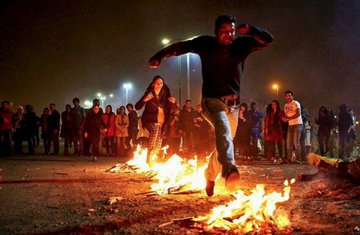

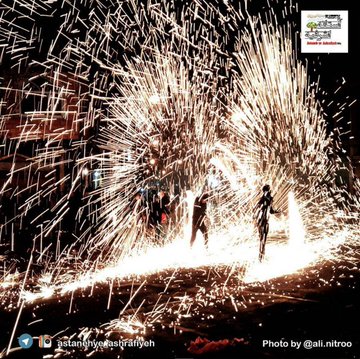

The last Tuesday before Norwuz is known as shab-e chahar shanbeh suri (a loose translation from Persian into phonetic English), or “Eve of Red Wednesday.” The day involves building public bonfires, jumping over them, and repeating a single phrase: “Zardi-ye man az toh, sorkhi-ye toh az man!” This roughly translates to, “Give me your beautiful red color, and take back my sickly pallor!”

The idea, in keeping with Nowruz’s overarching theme of renewal, is to cleanse away the past year so you can start the new one refreshed and renewed.

Children and elders make out especially well during Nowruz. At the beginning of the 13-day celebration, families will gather at the home of their oldest family member to pay their respects. Children will walk up to houses with cooking pots in hand, bang on those pots with spoons, and not let up until someone comes out and puts something sweet in the pots. (Like an Iranian version of Halloween, except you don’t have to dress up as a vampire to get your candy; you just demand what’s yours.)

Finally, children will receive monetary gifts in the form of fresh banknotes from their parents and other adult family members — again, in keeping with the overarching theme of getting a fresh start.

Okay, it’s all about freshness and renewal. But what about the food?!

Ohh, reader. Let’s talk about food.

If you’re not familiar with Persian cuisine, the very basics are that if you’re invited to an Iranian home for dinner you’ll likely be served some combination of grilled or braised meats and rich stews, flavored by deeply aromatic spices (though not many of them pack much heat) and accompanied by piles upon piles of steamed rice. (Persian rice is the best rice, and I will hear no arguments to the contrary.) For more on Persian food and ceremonies, you can check out Najmieh Batmanglij’s beautiful, thorough cookbook Food of Life.

On the actual day of Nowruz, though, you can expect to see a couple of dishes that are specific to the holiday, often centering on greens and herbs to represent its themes of — say it with me now — freshness and renewal.

The centerpiece of most Nowruz meals will be sabzi polow ba mahi, an herbed rice served with some kind of whitefish. Then you might have a kuku sabzi, which bakes eggs with a whole mess of herbs like dill, cilantro, parsley, fenugreek, tarragon, and more. (My mother helpfully describes kuku sabzi as “an ancient relative of the frittata.”)

No matter what, though, Iranians will always make you more food than you know what to do with — and at the end of the meal, you’ll still wish you could still eat more.

Above all, Nowruz is a celebration of the possibility of new life

As is fitting for Persian and Zoroastrian culture, the ceremonies surrounding Nowruz center on community, family, and a deep respect for tradition.

But Nowruz is less about a single day than a general celebration of being able to wipe away the dust, grime, and sadness of the old in order to start anew. It’s about closing the door on one chapter and turning the page to the next one with excitement instead of trepidation. It’s about the endless possibilities that come with a blank slate.

The hope of being able to start new, and better, is about as universal as they come — which might explain why Nowruz hasn’t just survived through generation upon generation of tumult and prosperity alike, but thrived.

Comments:

Post Your Comment: